IBD, IBH and Immunosuppression

By Dr. Linnea Newman

Features New Technology ProductionA Broiler Producer’s Guide to Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) and Inclusion Body Hepatitis (IBH)

A Broiler Producer’s Guide to Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) and Inclusion Body Hepatitis (IBH)

Double-digit mortality. Too many down birds and culls. Uneven flocks. Low-grade bacterial problems in the legs or the airsacs. Below average weight and feed conversion.

Double-digit mortality. Too many down birds and culls. Uneven flocks. Low-grade bacterial problems in the legs or the airsacs. Below average weight and feed conversion.

All of these problems can be the consequence of broiler management mistakes – but they can also be the visible evidence of silent diseases. The flock may be suffering from a compromised immune system or “immunosuppression” caused by a virus. This disease is called Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) or Gumboro Disease. A sudden spike in mortality with rough, uneven birds may indicate another viral problem: Inclusion Body Hepatitis (IBH). These two viral diseases have been on the rise across Canada, independently and together. An alert producer should recognize these problems and take appropriate steps to protect his or her investment.

Infectious Bursal Disease

IBD is caused by a tiny virus composed of two strands of RNA – and not much else. This means the virus is practically bomb-proof: there is nothing for a disinfectant to latch onto, so the virus is difficult to destroy. IBD virus is resistant to a wide range of pH (it can be destroyed at very high pH [12], but is unaffected by acidic pH as low as 2). It is resistant to disinfectants (phenolic derivatives and quaternary ammonium compounds had minimal effect when tested) and to extremes of temperature (it has survived five hours at 56°C!).

IBD can become a permanent resident even if farms are carefully cleaned and disinfected every flock.

What does IBD look like in my flock?

What does IBD look like in my flock?

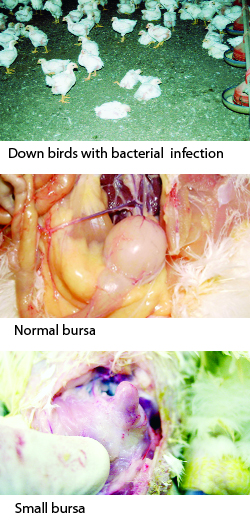

Broilers rarely show outward signs of the IBD infection itself. Instead, they become much more susceptible to other diseases such as bacterial infection with E. coli or viral infections like bronchitis or inclusion body hepatitis (IBH). Each of these other diseases can occur independently in broilers, but if the immune system has been hurt by IBD, the diseases may be more severe or may become chronic, causing increased mortality and culls through the life of the flock.

How do I know if I have IBD?

A veterinarian can look for evidence of IBD antibody in the blood of flocks at slaughter.

But even if antibody is present, it doesn’t always indicate that there is a significant problem. The place to look for the problem is the bursa of Fabricius itself. Any damage to the bursa before 21 days of age causes significant, permanent damage to the immune system. If the bursa is healthy beyond 21 days, the flock will only demonstrate a short- term depression of the immune system when IBD strikes. A good place to begin evaluation is to examine the bursas in 28-day old flocks. If IBD infection occurs even later, the flock may be on its way to the processing plant before any negative effect is felt.

What and where is the bursa of Fabricius?

The bursa of Fabricius is a round organ located just above the intestine at the vent. It is the heart of the bird’s immune system; the place where all of the lymphocytes (the cells that will produce antibody) are formed. When it is attacked by IBD, the lymphocytes inside of the bursa die, and the bursa shrinks (atrophies) and scars.

A producer can submit 28-day-old birds to their local veterinarian for examination.

Choose five random, healthy birds. Avoid cull birds and sick birds, which often have small bursas due to stress. The random birds can also be examined for intestinal health and coccidiosis control, so a 28-day post-mortem is a good tool for examination of both gut and bursal health.

A good bursa in a 28-day-old bird may approach the size of a quarter. A poor bursa may be smaller than a dime.

What does IBD look like?

A bursa that has been infected with IBD may have several appearances: yellowish, hemorrhages, “beach ball”-like or just plain small.

Inclusion Body Hepatitis. What is Inclusion Body Hepatitis (IBH)?

Inclusion Body Hepatitis is caused by a different virus, a Type I adenovirus. Adenoviruses are very common in the poultry environment, and usually the pullet flocks develop immunity to them before they ever move to the breeder house and begin to lay eggs.

When an adenovirus causes disease in chickens, the disease is called “Inclusion Body Hepatitis” or IBH. It’s called “hepatitis” because the liver swells and may become discoloured. “Inclusion Body” comes from a hallmark sign the pathologist sees when they look at the liver microscopically: little dark dots in the nucleus of the liver cells. Many types of bacterial and viral infection can cause the liver to swell, but the dots or “inclusion bodies” tell the pathologist that adenovirus is involved.

Flocks affected by IBH often experience severe stunting in a percentage of birds, and excessive mortality for a period of a week or two. After the affected birds die, flock uniformity may remain an issue, but mortality returns to normal levels. Sometimes flocks become more susceptible to secondary bacterial infections during the IBH outbreak, but this may be caused by simultaneous infection with IBD

How do I get IBH in my broiler flock?

Broiler IBH can occur under two circumstances: 1) IBH adenoviruses may shed from an infected breeder flock into their broiler progeny or 2) uninfected broiler progeny without maternal antibody may become infected when placed on a broiler farm harbouring the IBH virus. Most replacement pullet flocks are exposed to adenoviruses early, and immunity develops long before the flocks ever start to lay eggs. If the pullet house is very clean, however, the pullet may never become exposed early in life. When the naive pullets become exposed later in life, they begin to shed the adenovirus into the eggs that they lay. If the breeder flock experiences a significant exposure to adenovirus while laying eggs, they may shed adenovirus heavily for a short period of time until they become immune. Broilers from these hens will often develop signs of hepatitis at a young age (seven to 14 days of age).

If the exposure is minimal, only a portion of the birds may shed adenovirus into the eggs. A handful of broiler chicks from these flocks may be the only ones that harbour the virus. These chicks can serve as the seeds for infection in the broiler house, slowly spreading the virus to their hatchmates or to the progeny of other breeder flocks placed in the same house. The infection will often smolder in the flock until it finally reaches a threshold level where it causes hepatitis, often at four to five weeks of age.

Immune system damage from IBD (Gumboro) can help to push these broiler flocks into full-blown IBH disease. Breeder flocks with low-grade infection may continue to shed low-level adenovirus for a long time before every bird in the flock finally becomes exposed and develops immunity.

Once a broiler farm has experienced IBH, the virus may become resident on the farm. If this happens, then new placements from IBH-negative breeder flocks may become infected at the broiler house itself. These flocks will tend to break with signs of IBH at four to five weeks of age because it takes time for the virus to reproduce in the chicks.

Why is IBH a problem in Canada?

Canadian flocks are clean; perhaps too clean. Pullets are not always exposed to adenovirus early in life, so they remain susceptible. If breeder houses remain unexposed, there’s no problem. If, however, the breeders become exposed at any time during their long lives, they can begin to shed the virus to their progeny. Adenovirus, or a new strain of adenovirus, has slowly been making itself felt across Canada from east to west over the past few years. Scientists do not yet know how it has been introduced to our flocks, but they have been watching its progression across the provinces.

What is the connection between IBD and IBH?

Historically, broilers could become infected with adenovirus and never show any signs of disease at all. IBH disease with hepatitis and poor flock uniformity would only occur if the broilers had a compromised immune system – usually because they had been infected with IBD virus. The adenovirus currently affecting Canadian flocks appears to be able to cause IBH disease even without immunosuppression due to IBD, but the impact of the IBH can still be dramatically enhanced if IBD is present.

Variant IBD on the rise

While IBH is spreading across Canada, IBD is also becoming a greater concern. The IBD virus is capable of mutation, resulting in variant forms that attack the flock earlier, causing more severe damage to the immune system. Variant IBD was first identified in samples from Quebec and Ontario in 2002, but variant type IBD viruses are now being isolated in western provinces as well. The presence of a variant type IBD on a farm increases the susceptibility to all diseases, including IBH.

Can’t we just vaccinate our pullets with an IBH vaccine?

Early pullet exposure to adenovirus with a live vaccine is needed – but no such vaccine exists at this time. Scientists at the University of Saskatchewan and the University of Guelph are working on a licensed vaccine for Canadian flocks, but a vaccine isn’t imminent. There are no commercial IBH vaccines available in the U.S. at this time, either.

“Vaccination” of new pullet flocks with litter from adenovirus-positive flocks is a risky practice that might be attempted with the oversight of a veterinarian. Such litter might provide the necessary exposure to adenovirus, but it will also expose pullets to other pathogens, such as salmonella. This should never be attempted without proper veterinary oversight.

Autogenous killed vaccines might be created with the help of a U.S. vaccine company and your veterinarian. Autogenous vaccines are custom-made from a virus isolated from the farm or region to be vaccinated. The process is difficult and costly, but has been undertaken in at least one Canadian province.

Is there a treatment for IBH?

No. This viral infection will run its course with stunting.

What can a broiler producer do?

The answer is the same for both viruses: protect your flocks against IBD, especially the new variants of IBD on the rise in Canada. Reducing the immunosuppression from IBD infection will help defend the flock against all diseases, and may reduce the impact of IBH exposure.

A protective IBD vaccination program should be designed with the help of your veterinarian. The vaccine you choose, the route of administration and the timing of vaccination are all important to the success of a program on your farm.

Designing an IBD Program

1. Determine if IBD is a problem your farm

Twenty-eight-day-old birds, or bursal tissue samples from 28-day-old flocks can be submitted to a veterinary laboratory for examination. If the bursas show signs of damage at this age, the veterinarian can help you with additional tissue samples and serology.

2. Be alert to variant IBD viruses

The first sign of the presence of variant IBD on your farm may be bursal damage despite a good IBD vaccination program. The veterinarian can confirm the presence of variant type IBD by submitting samples to Guelph University laboratory for a technique called RT/PCR-RFLP.

RT/PCR-RFLP (often just called “PCR”) is a new laboratory test that uses enzymes like scissors to cut the RNA of the virus into fragments. Imagine a paragraph of text: if we used scissors to cut the text wherever we have two vowels in sequence, we’d get text fragments of varying lengths. If we did the same thing with a different paragraph, we’d get text fragments of varying lengths again, but the lengths would be different from the first paragraph. Without ever seeing the words themselves, we could compare the pattern of fragment lengths and know if we have an identical paragraph of text or a different one. This is how scientists can tell us whether the viruses are similar or very different from one another.

Using this technique, scientists have identified six known molecular groups. Three of these (Groups 3, 4 and 5) are considered “classic” IBD strains and three (Groups 1, 2 and 6) are considered “variant” type IBD strains. The variants tend to be more aggressive viruses, causing much earlier bursal atrophy and more severe immunosuppression.

Vaccines designed for protection against the classic strains may only give partial protection against the new variants. Multi-antigen classic vaccines (two or more different viruses) provide better cross protection against many variants than single-antigen vaccines.

3. Choose a vaccine that’s right for your farm

Broiler IBD vaccines are mostly considered “intermediate strain” products. Some are produced in tissue culture, and some in eggs. Tissue culture vaccines are sometimes milder, and safer to use in the hatchery. Vaccines produced in eggs may sometimes be more “antigenic” (the immune system responds more strongly to them). But each vaccine has its own spectrum of protection and strength.

IBD vaccines containing true variant viruses have recently been licensed for use in Canada, enhancing our choices for variant IBD protection.

Although I am a veterinarian employed by a vaccine company, my preference is to use the mildest vaccination option that still works. If you have no challenge on your farm, and there is no evidence of IBD challenge in your region, don’t vaccinate. If other farms in the area are affected, use vaccination as insurance, but use the mildest, classic strain vaccine that is effective.

When single-antigen tissue culture vaccines do not work well, try an egg-derived vaccine. If a variant has been isolated in your area, try a double-antigen classic vaccine before introducing a variant vaccine. Always remember that IBD is “bomb-proof”: we don’t want to introduce viruses, even vaccine strains, if it isn’t necessary. If a true variant challenge is already present on your farm, use the new variant vaccines or a double-antigen classic vaccine.

4. Rotation of vaccines

Scientists theorize that the variant-type IBD viruses first arose on the Delmarva Peninsula of the U.S. because intensive vaccination against classic IBD effectively prevented the classic IBD virus from multiplying. This left the door open to variant sub-populations to grow and become dominant. We may be able to influence our own farm populations by rotating vaccines to avoid using the same vaccine virus for too long. Farms being vaccinated with variant IBD vaccines may benefit by rotating to a double-antigen classic vaccine in an attempt to re-seed the houses with classic strain. Farms vaccinating with a single-strain vaccine of one molecular group may benefit from a switch to a single-strain vaccine of a different molecular group to surprise any growing virus subpopulation.

5. Timing of vaccination

Timing of vaccination is critical to making an IBD program work. A recently reported study demonstrated that hatchery vaccination could delay the onset of IBD damage to the bursa by four to six days compared to a high level of maternal antibody alone. Although hatchery vaccination helped significantly, the challenge virus was still able to break through well before 21 days of age. A field boost was still necessary.

The variant IBD challenge virus was capable of attacking the bursa as early as nine days of age through maternal antibody and 15 days of age with maternal antibody plus in-ovo vaccination. Field boosting may need to be early (eight to 12 days of age) to be effective. For many licensed IBD vaccines, this is extra-label use. The producer must work closely with their veterinarian to obtain the appropriate use recommendations, prescription, withdrawal time and C.G. FARAD opinion so the flock sheets can be properly completed.

Conclusion

Inclusion Body Hepatitis and variant IBD are both on the rise in Canada. We have the tools, including new vaccines and new research that will help us to design effective vaccination programs against the variant IBD problem.

Inclusion Body Hepatitis is more difficult: Canadian scientists are still hard at work to create a new vaccine for Canada. At this time, we can only rely upon good biosecurity and a solid IBD protection program to ensure maximum function of the immune system. There is hope: autogenous IBH vaccines produced for individual integrated companies in the U.S. have proven highly effective.

References

1) McCarty et. al. 2005. Delay of Infectious Bursal Disease Virus Infection by In Ovo Vaccination of Antibody-Positive Chicken Eggs. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 14:136-140.

2) D. Ojkic et. al. 2003. Molecular Characterization of Ontario IBDV Field Strains. University of Guelph AHL Newsletter Vol. 7, no. 1 pg 6.

3) B.W. Calnek (ed.). 1997. Diseases of Poultry 10th edition. Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA.

Print this page